Dear reader, if only you knew how many hours I’ve been staring at this empty Word document. I’ve been procrastinating in the most creative ways, only managing to do the bare essentials, then staring blankly at the same white page on my screen. I daydream frequently of an hourly wage, after all breaking through a creative block takes time, energy, and skill, and it’s also part of the creative process. An underestimated and sometimes crucial part, a barrier that those who don't create may never notice or need to overcome. I wouldn’t call it a privilege, but maybe an opportunity sounds more convincing. Not only the opportunity to create something after breaking through that block, but also the opportunity to reflect on your recent lifestyle — essentially, to look at yourself. From my experience in journalistic, academic, and creative writing, I’ve noticed that I usually hit a block during overloaded periods.

This week has been packed with academic writing and intense brainwork, leading to sleepless nights, not to mention all the not so trivial everyday matters. A more stressful week at this stage of my life means handfuls of hair falling out, a grey, raisin-like complexion, bloodshot eyes, a foggy head, and... idiots everywhere. Probably nothing new to anyone. Often, I try to suppress this state not by reducing the load, but quite the opposite, by indulging in a cosmic amount of scrolling. Chronicles of the zombie.

At 21, I more than flirted with the slower, idealistic dream of monastic life. Although that's a story for another time, it comes to mind now because of the then youthful and religiously maximalist mental hygiene practices, the very clear understanding of how one’s lifestyle affects well-being, likely in the afterlife too, and the longing for a quiet life with a mission. It’s impressive to recall the spiritual and physical discipline I once had, at a level that seemed like a natural or even necessary element of the chosen way of life. I see many similarities between the monastic path and the life of a creative person. For example, both require discipline. By adhering to it, you can at least temporarily distance yourself from a distracting world and fully, in body, spirit, and mind, commit to the mission. Maybe one day I’ll dare to write more about practices that I believe could be adapted to the lives of people occupied with worldly missions, but there’s one I must share today.

Pay attention to what you feed your eyes, ears, and mind. What you consume, you become. The connection between food and health, longevity, and overall quality of life is often self-evident. Unfortunately, when it comes to consumed content and its quantities, I still find myself proving this to myself every day. Sometimes in the most unexpected ways.

The other day, I got terribly triggered; I couldn’t stop thinking about a sight I had seen. On my way back from my daughter’s kindergarten, I passed a woman pushing a stroller with what seemed to be a 2-3 month-old baby. In these cases, I try to catch the eye of a woman who has recently become a mother (whether for the first, second, or nth time) and telepathically send a message of support. I vividly remember how tough that stage was and how much I needed those supportive glances from other mums. A cocoon lying on its side in the bassinet with a dummy in its mouth, watching a flashing animation on a phone. I guess the baby was fussing because of a dirty nappy, hunger, or lack of attention. Not fussing anymore. Babies of that age are just starting to distinguish some colours and, in general, to follow moving objects with their eyes, like the silhouette of their mom or dad moving in the room. The sight completely threw me off balance. Honestly, I couldn’t find it in me to judge the baby’s mother, I just felt sorry for the baby and hurt by the situation.

The average child in Lithuania spends two or more hours a day staring at screens, it’s already an integral part of their daily routines. I’m not a screen-averse “supermom,” I don’t think a couple of cartoons for a toddler who can walk on their own or a video game for a teenager will ruin their life, though I might hold a slightly more conservative opinion when it comes to phones. However, excessive screen time is a threat to healthy physical and psychological development, there are long-established links to sleep and attention disorders, a lack of social skills, and emotional detachment. Screens become a digital filter, altering the perception of the world around us. For babies, these changes are especially dangerous, as they are just learning to recognis

e themselves, emotions, their surroundings, their parents’ bodies, and screens stifle these most fundamental developmental processes.

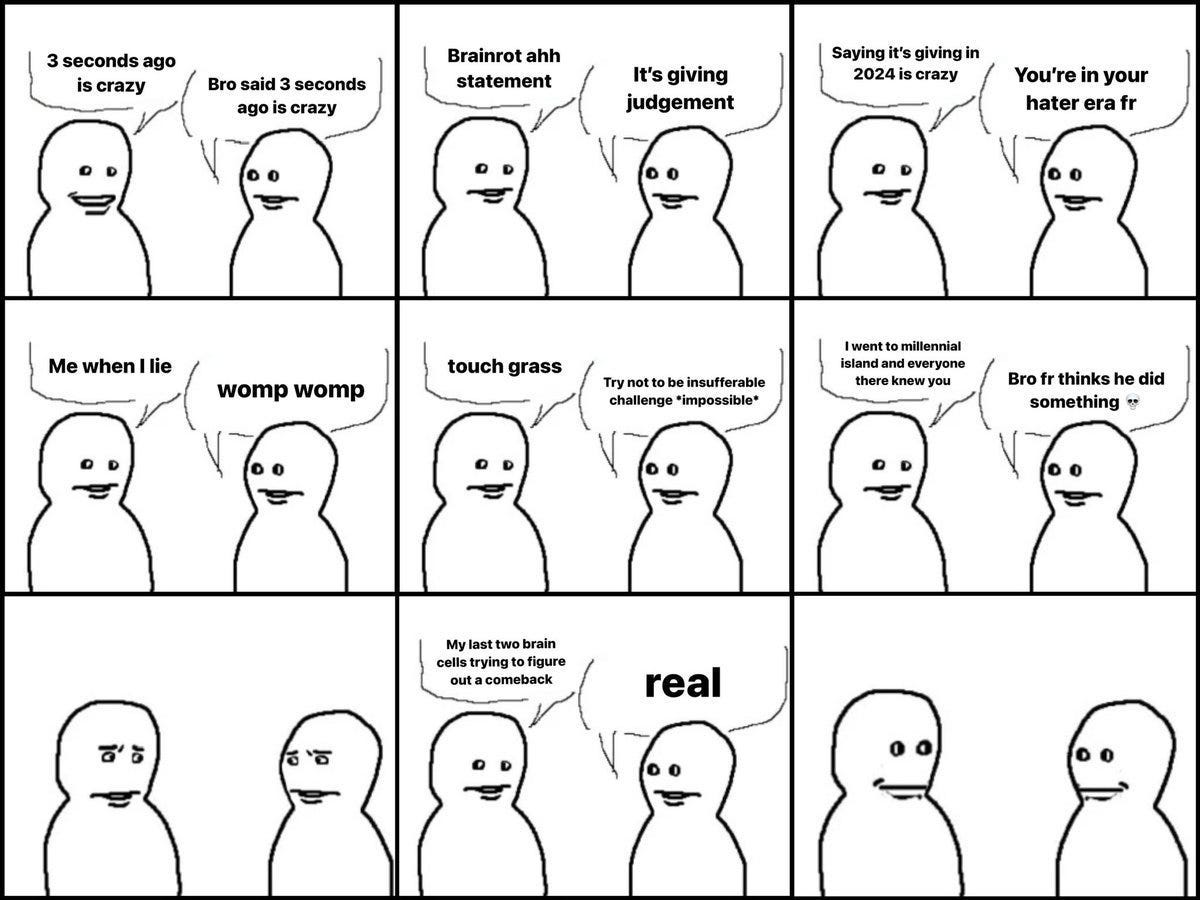

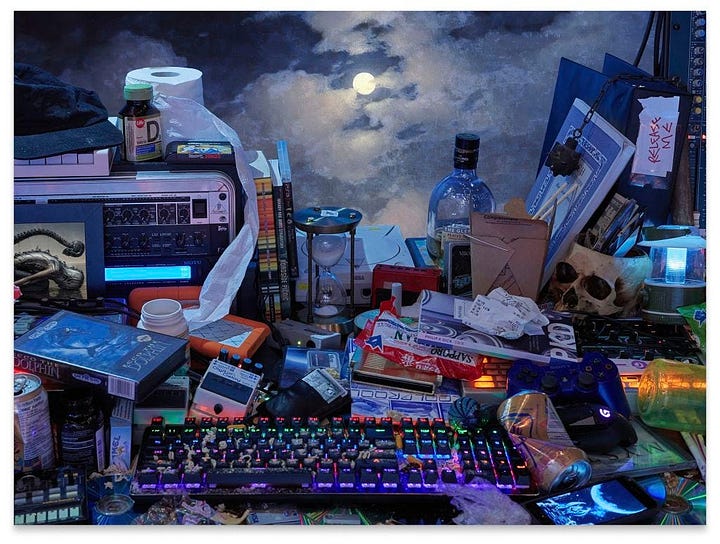

Currently, the most-watched content among kids and teens is what is often referred to as brainrot content. It is absurd, meaningless, sensory-overloading content, most common on platforms like TikTok and YouTube. These types of videos, Skibidi Toilet being a prime, specific example or the corecore genre as a more broad one, present a mix of images and sounds with no clear logical structure or meaning. These videos are characterised by fast cuts, fragmentation, and often hyperbolized, absurd situations that go far outside typical limits, warping what is being depicted beyond recognition. This kind of content is momentarily entertaining and increasingly captivates both children and adults. Due to the high level of sensory stimulation, frequent consumption of brainrot content leads to so-called ‘information burnout’, simpler or slower activities become unbearable.

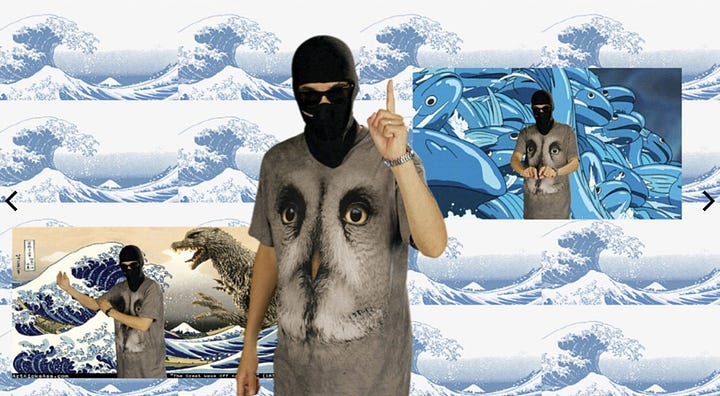

Contemporary art has long explored the overload of information and imagery we all experience, and brainrot content is an expression of this trend in popular culture. Canadian artist Jon Rafman uses digital collages to comment on informational chaos and technological overload. His works often consist of popular online images, computer games, and other digital sources, which together create a new virtual reality.

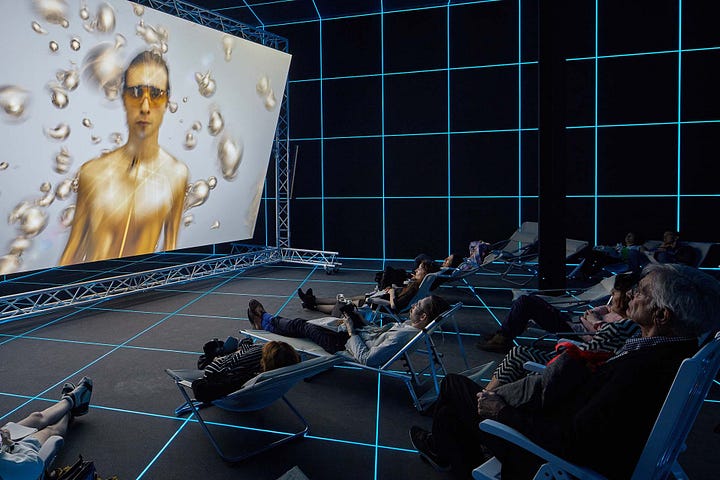

German artist and filmmaker Hito Steyerl focuses on the role of media, technology, and image circulation in the era of digital nativism (digital natives are people who have grown up surrounded by technology, making it feel natural to them). The artist creates installations where cinema is linked to the construction of architectural environments. Aesthetically, his works again resemble brainrot content.

Until October 6th, you can still visit Rūtė Merk’s exhibition “Promises” at the National Gallery of Art in Vilnius, which I briefly wrote about in the Vilnius Gallery Weekend newsletter. The artist also uses the aesthetics of digital collages, with blurred visuals of AI-generated faces and bodies. This aesthetic is reminiscent of brainrot content, where chaotic images and meaningless fragments merge into sensory noise. Contemporary art explores the problem of excess, and brainrot content can be understood as a cultural product of such excess.

One of the more interesting discussions is whether this type of digital content can be considered a form of contemporary art. At first glance, it’s just entertainment, but upon closer inspection, certain artistic features can be found. Brainrot content not only conveys a chaotic flow of information but, through its absurdity, may provoke thoughts about screen addiction and the uncontrollable dopamine buzz. That’s exactly the kind of thoughts I had after watching Skibidi Toilet. Share yours if you decide to explore this new way of killing off brain cells.

Perhaps brainrot content is a reflection of modern life, it acts as visual noise that we voluntarily surround ourselves with, searching for quick and effective escape. So, while such content may seem absurd and superficial, it inspires contemporary artists, operates on similar aesthetic principles as recognised works of art, and can be interpreted as a reflection of the current zeitgeist. I invite you to share in the comments whether you think brainrot content could be considered an artistic expression of the digital world.

Honestly, this text kind of turned out brainrot-like itself — from a baby’s cradle entertainment to monastic practices to art — but I guess that’s the price of conquering a white page that’s been looming for way too long.

See you soon,

Galerista